Alaska Native People & Cultures

By knowing your past, you will see the future —Dena’ina saying

Alaska Native people are the indigenous communities of the sub-Arctic lands we call Alaska.1

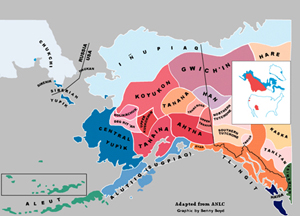

The term Alaska Native represents 11 distinct cultures and languages, and 22 different language dialects.

The Iñupiaq and Yup’ik people are also connected to other indigenous communities of the international circumpolar North, such as the Saami and Inuit. The historically common word Eskimo is used by some Alaska Native people, while others find it offensive. We use the most specific description of a person or community (i.e. Gwich’in or Tlingit) rather than broadly Alaska Native.

Alaska Native communities and experiences can be separated by 900+ miles and are correspondingly diverse. The state’s 533,000 square miles are spread over almost 20 degrees of latitude, making it twice as large as Texas, with a total coastline equal to that of the rest of the U.S. combined. Of the 20 highest peaks in the U.S., 17 are in Alaska, along with more than 70 potentially active volcanoes and an estimated 100,000 glaciers. Human beings have survived and thrived in the different ecosystems of this beloved landscape since time immemorial — more than 14,000 documented years — through innovation and development of highly adaptive technologies for transportation, food preservation, protection from the elements and more.

Alaska Native communities and experiences can be separated by 900+ miles and are correspondingly diverse. The state’s 533,000 square miles are spread over almost 20 degrees of latitude, making it twice as large as Texas, with a total coastline equal to that of the rest of the U.S. combined. Of the 20 highest peaks in the U.S., 17 are in Alaska, along with more than 70 potentially active volcanoes and an estimated 100,000 glaciers. Human beings have survived and thrived in the different ecosystems of this beloved landscape since time immemorial — more than 14,000 documented years — through innovation and development of highly adaptive technologies for transportation, food preservation, protection from the elements and more.

Alaska Native People & United States Policy

Like other indigenous peoples whose existence in North America precedes the United States and Canada, Alaska Native people have a unique government-to-government relationship with the United States reflecting their status as sovereign tribal nations.

Instead of the system of reservations in the Lower 48 (or reserves in Canada), and in addition to the 231 village tribes, the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA, 1971) created a system of 13 regional and over 200 village based for-profit corporations. Related regional non-profit tribal organizations providing housing, educational support, and other social services to tribal members and descendants.

Alaska Native people have had to contend with colonial policies intended to obliterate our languages, way of life and title to traditional lands. Despite this, our cultural connection and commitment to language revitalization remain strong. Subsistence food harvests are an essential component of rural economies and the food security of many urban families. After English, Yup’ik is the most commonly spoken language in Alaska. New tools are developed regularly for those learning and speaking Alaska Native languages, from online dictionaries and smartphone apps, to word-of-the-day programs on local radio and public television.

Knowing the Past, Seeing the Future

The oldest continuously occupied settlement in North America is near Point Hope, an Iñupiaq village 330 miles southwest of Barrow, above the Arctic Circle. The oldest record of human life in Alaska—also older than anything known in the Lower 48—is the cultural site at Swan Point, north of Delta Junction.

The idea that Alaska Native people are disappearing is a myth. To the contrary, we are a strong, vibrant and growing population. There are more than 138,000 people who identify as Alaska Native living in Alaska—almost 20 percent of the state’s total population.

Alaska Native people are political and business leaders, educators, engineers and service providers throughout the state. No single idea could define us or our families, but we remain Alaska’s First People.

Additional Resources

Alaska Humanities Forum: AK History & Cultural Studies – www.akhistorycourse.org

Alaska Native Heritage Center – www.alaskanative.net

University of Alaska Anchorage: Alaska Native History & Education site – www.alaskool.org

University of Alaska Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center – www.uaf.edu/anlc

Arctic Studies Center – http://www.mnh.si.edu/arctic/html/resources_faq.html

1. A native Alaskan, on the other hand, is any person born in Alaska.